Welcome to Lab Session 4: An Introduction to AWK

For this lab session we’re getting started with the AWK programming language!

The lecture notes for lecture 4 can be found here.

You should complete the exercises from Lab Session 03 if you haven’t done so already. If you only complete Part 1 and 2 of Lab Session 03, that’s fine for now. It’s also OK to wait with Part 3, and instead do those exercises as exam preparations.

An Introduction to Language Processing with AWK

What is AWK?

AWK is a data-driven programming language designed for text processing and data extraction. It has a simple syntax and is easy to learn, at least compared to other programming languages. Despite the fact that AWK is more than 40 years old, it is loved by system engineers, language researchers, software developers and data scientists because it makes a lot of complicated text processing operations very easy to do in just a few lines of code.

When talking about the AWK programming language, we use capital letters - AWK. When talking about the Unix command, we use lower case letters - awk. The awk command takes AWK code as input. Keep in mind that most of what we’ll be doing today will also work in GNU AWK, known as gawk. gawk has some additional functionality which I will not go into here, but know that you can try to use gawk instead of awk if something doesn’t work properly for you. gawk first, Google later!

If you already know some programming, you’ll find many things in AWK familiar. This is especially the case if you are familiar with other dynamically typed languages such as Python or Javascript. Keep in mind that there are a few significant differences as well, but regardless, you should be able to pick it up quite quickly.

If you’re new to programming, AWK might seem a bit overwhelming at first. However, AWK is a great first programming language to learn, because it is quite forgiving and pretty easy to get started with, even compared to languages like Python or Javascript.

The general syntax of AWK is like this:

awk 'PATTERN { ACTION }' FILENAME

awk tells the shell to execute the code with the awk program. PATTERN can be any pattern such as a regular or logical expression, which tells awk which lines or string sequence to perform the action on. The pattern can also be left empty. ACTION denotes the action or series of actions to perform on the (matched) input. FILENAME is just the name of the file to be used as input. We can also pipe / direct input from other UNIX commands, just like every other command we’ve gone through thus far in the course.

In other words, awk loops over the input file line by line, and executes the specified action on the matched lines/words/characters.

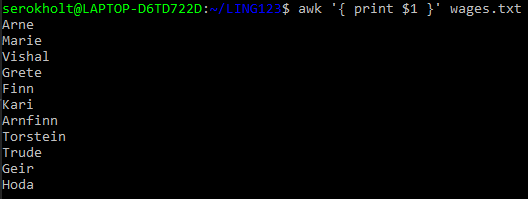

Here’s an example. I have a simple file called wages.txt which contains information about the employees in my small business. It has fields (columns) for the employee’s names, hourly wage and the amount of hours they have worked this month.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

Arne 182 0

Marie 190 0

Vishal 213 150

Grete 192 16

Finn 192 37

Kari 220 145

Arnfinn 220 150

Torstein 250 132

Trude 196 150

Geir 160 13

Hoda 196 42

I want to compute the monthly salary for each employee, but only the ones who have worked more than 0 hours. This is easily done with awk:  Computing the monthly wage with awk

Computing the monthly wage with awk

Now, I dare those of you who know Python or Java or most any other programming language to achieve the same thing in a single line of code! This example shows a glimpse of just how elegant AWK can be.

Let’s dive in to the specifics.

Fields and field separators

I mentioned that awk loops over the input line by line. What makes awk really handy, is that it partitions/separates the input lines into different fields. These fields can be referenced in the code by using the dollar sign $ and the field number. Like this:  Printing the first input field with awk

Printing the first input field with awk

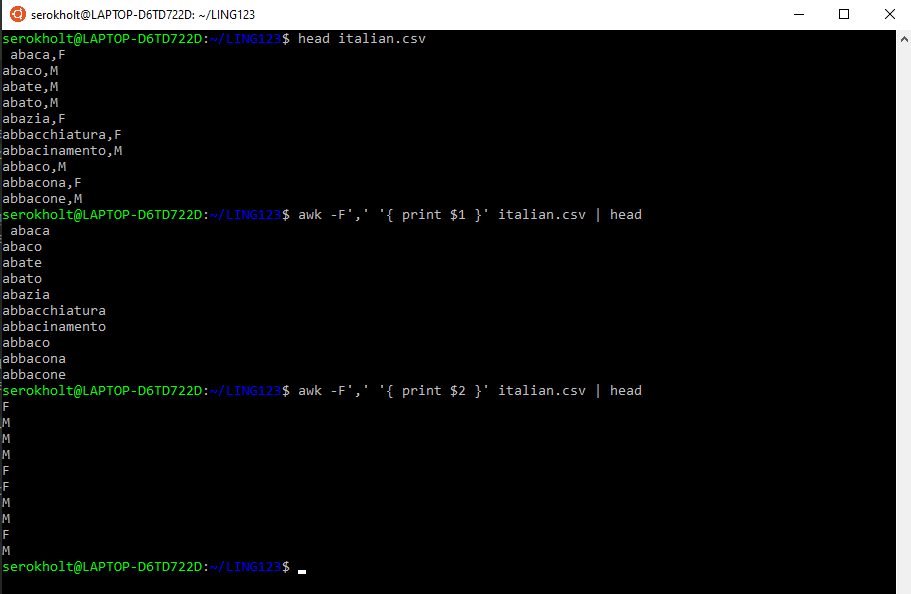

You can also print the whole line with $0, the second field with $2, the third field with $3, and so on. The default field separator is set to space, but can easily be changed by specifying a new one with the -F option:  Setting a new field separator

Setting a new field separator

Patterns

If we only want to match the lines according to some logical or regular expression, we enter a pattern before the curly braces which denote the action. This means that the action will only be performed on the lines matching the pattern.

If I only want to print the names of the employees who have an hourly wage over 200.-, I can specify a pattern with a logical comparison like this:

Or I can specify a regular expression by enclosing it in slashes, like this:

Actions

There are a LOT of different stuff you can do with the matched input. You can write one-liners or looooong scripts/programs with AWK. Here’s just a few examples of techniques/tools/possibilities you can use when writing AWK code:

- Create and assign variables with

= - Mathematical expressions with mathematical operators, such as addition

+, subtraction-, multiplication*, division/, exponents^and modulus& - Use logical operators such as “AND”

&&, “OR”||, “NOT”!, “EQUALS”==, and “GREATER OR EQUAL THAN”>=, “NOT EQUAL TO”!= - Control flow such as

if,else if,else,for, andwhile - Using built-in functions, such as

print,tolower,toupper,return,sub,length,split,exitanddelete. - Regular expressions

We will take a further look into some of these today, and you will likely encounter many more later in the course. Make sure that you are familiar with the ones used in the lab exercises, as these are much more likely to be used in exam questions.

Built-in variables

AWK comes with many built-in variables, which are already defined and ready to use without any setup.

NF

The NF variable represents the number of fields in the current input line (record/row). By default, each field is separated by a space, but it can be specified with the FS variable.

1

echo -e "En To\nEn To Tre\nEn To Tre Fire" | awk 'NF > 2'

This gives the following result:

NR

The NR variable represents the index number of the current input line (record/row).

1

2

3

4

5

echo -e "Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveler, long I stood

And looked down one as far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth; " | awk 'NR == 1'

In this example, the newlines are denoted with pressing the Enter key, so you can’t see them in the terminal. But they are there, and the field separator still knows what to do. Here, I specify that I want to return the first line in the poem:

FS

The FS variable represents the input field separator and its default value is the space " ". It works very similarly to the -F option. Here’s an example:

Built-in functions

awk comes with many built-in functions and variables which are ready to go. You should already be familiar with tolower, which converts an input string to lower case.

print and printf

So far, we’ve mainly used print which just prints the (matched) input string to the terminal. We can give print a string argument directly, and also combine it with using fields, like this:

awk '{ print "The total pay for ", $1, " is ", $2 * $3, "\n" }' wages.txt

Take note that string arguments are denoted with “double quotes”. We can also accomplish the same thing more elegantly with the formatted print, printf:

awk '{ printf("The total pay for %s is %.2f kroner \n", $1, $2 * $3) }' wages.txt

Here we need to give printf the entire expression as an argument enclosed in parentheses. We also need to specify that we want a new line \n character at the end of each line.

length

We can print the lines for employees with a name longer than 6 characters like this:

awk 'length($1) > 6' wages.txt

split

The split function takes a string as input and splits it into fields using a regular expression as field separator. If the regex is emitted, the normal field separator is used. The split function takes three arguments: str, an array arr and an optional regular expression regex: split(str, arr, ","). This will split the string where a comma occurs, and save the result in an array. We can then print the array to the terminal, like this:

awk 'BEGIN {

str = "en,to,tre,fire,fem"

split(str, arr, ",")

print "Array contains following values"

for (i in arr) {

print arr[i]

}

}'

Options

The awk command takes options, just like grep or sed or most other UNIX commands. Here are the two most important ones, but remember that you can view all of them with man awk.

awk -f

The -f option tells awk that it should execute the code from an AWK script/file.

awk -F

The -F option is the “field separator string” which sets the FS variable. It tells awk what to use as the separator. You’ve already seen an example of how the field separator option can be changed, for instance to read comma-separated value(.csv) files.

AWK’s Workflow

To use AWK efficiently, you need to know the basics of workflow. When you are writing a longer AWK script, the workflow will often look like this:

- The BEGIN block is executed first.

AWK BEGIN {awk-commands} - The BODY block, or MIDDLE block, is executed for every input field / every input line.

AWK /pattern/ {awk-commands} - The END block is executed last. Similarly to the BEGIN block, it executes only once.

AWK END {awk-commands}

Here’s a simple example:  A simple AWK Workflow example

A simple AWK Workflow example

The BEGIN block is a great place to set variables, communicate with the user running the script, or to set ‘columns’ when you want the output of the script to look like a table. The END block is good for returning the end result of whatever you were doing in the main block, especially if you are iterating (looping) over something.

Here’s a new example, this time implemented as a script.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

#!/usr/bin/env bash

#filename: employee_count.sh

awk 'BEGIN {print "Starting...";

n_employees = 0}

{n_employees = n_employees + 1}

END { printf("There are %d employees in the company.\n", n_employees);

print "Program terminated. Have a nice day" }'

I can execute the script like this:

Okay, so here’s what’s going on in employee_count.sh:

- First we state that the script should be executed in the shell. This means that we also have to specify that we want to use

awkto run the code in the script. - We then create a variable

n_employees(number of employees in my business) and set it equal to 0. - We loop through the file, which in this case is given as input to the script when it is run in the shell. For every employee we find in the file, we increase the variable

n_employeesby 1. - Finally, we can print the result to the terminal in the END block.

One last thing before we go to the exercises. You can skip this part if you want, but this is something that kind of blew my mind when I first started learning AWK.

This line of code is equivalent to the script above, and will give the same exact output:

awk '{ n_employees++ } END { printf("\nThere are %d employees in the company.\n", n_employees) }' wages.txt

Not only can you use ++ to iteratively increase the value of a variable by 1, but you actually don’t have to set the variable to begin with. You just write n_employees++ and AWK just figures out that n_employees is a new variable with an integer data type, which you want to iteratively increase for every line in the input file.

That’s pretty neat.

Useful resources

- For reference: Tutorialspoint.com

- For historical and introductory information about AWK

- The O.G. AWK tutorial: The AWK Programming Language

- Why not use AWK for… everything?

Exercise 1: Counting columns with Awk

Look at the example from the lecture notes. The French examples d’information and l’agriculture are contractions of two words. Translate the apostrophe to a space before counting.

Exercise 2: Cutting columns and numbering lines

Extend the script, for instance with sed, so that you put a period after each number. Experiment with different formats. Reverse the columns in the last example, so that the numbers come after the words. This can be done by adding | awk '{ print $2 " " $1 }' after the nl command.

Exercise 3: Reverse dictionary

Check the alphabetical order for a few different languages.