Here are my solutions to the exercises from lab session 03.

You should try to solve the lab exercises yourself before you peek at the answers!

You can find the exercises to Lab Session 03 here.

Disagree with my solutions, or have something to add?

Leave a comment!

Part 1) Word frequencies and N-grams

Exercise 1.1: Script files and word frequencies

a) Recreate this example (tokenize.sh + count word frequencies) and send the output to a file. Compare this result with a frequency list obtained otherwise, for instance, with Antconc.

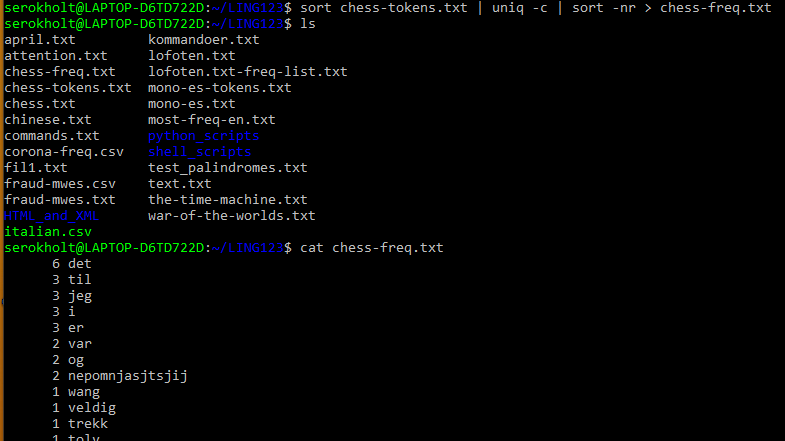

Creating a frequency list for chess.txt in the shell

Creating a frequency list for chess.txt in the shell

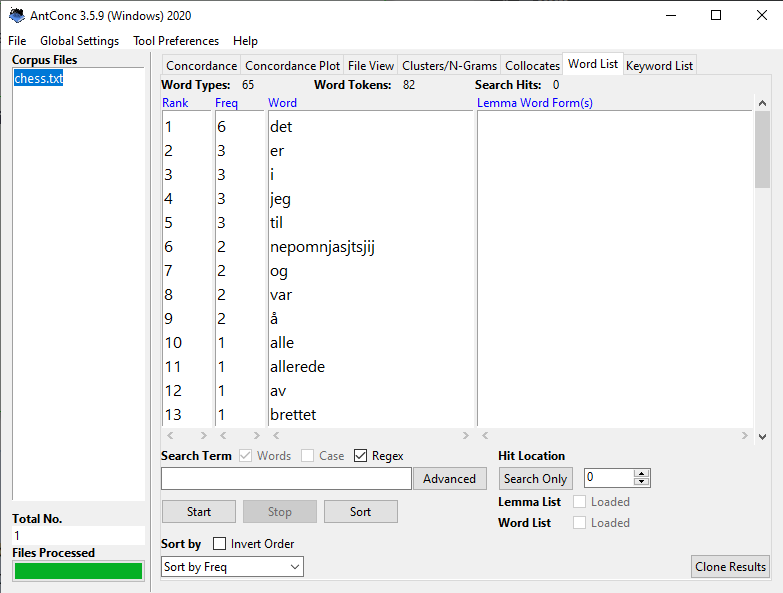

Frequency list for chess.txt with Antconc

Frequency list for chess.txt with Antconc

When comparing the frequency list to Antconc, we see that the output is mostly the same. The only difference, as far as I can see, is that Antconc sorts the occurences first by frequency, then alphabetically, while bash sorts the occurrences by frequency, then in reverse alphabetical order.

However, there might be other differences depending on the tokenization process in bash, such as that it might be necessary for you to specify how apostrophes should be interpreted. Antconc also has a lot more functionality, and enables you to easily sort by different parameters. It also provides a ranking of each word in the frequency list.

b) Create a script file freq.sh to make a frequency list of a tokenized file given as argument. Try to combine it with the script for tokenization.

A script which creates a frequency list of a file

A script which creates a frequency list of a file

c) Make a frequency list of a larger text, then select lines matching a regexp, e.g. words with three letters or less. How do frequencies of shorter words compare to frequencies of longer words?

Frequency by word length

Frequency by word length

We can select words that are three letters or less with the regular expression \b[[:alpha:]]{1,3}\b. If we sort the output with sort -k1 -nr, we can see the words with the highest frequency. When we execute the code for words of different lengths, we see that there is an exponential relationship between word length and number of occurrences in the text. Words of three words or less are much more prevalent (at least the popular ones) than words of four words, and words of four letters are much more prevalent than words with six letters, and so on.

Exercise 1.2: Plotting word frequencies in R

a) Recreate the example from the lecture notes in RStudio.

An RStudio plot of frequency by index (rank) for words in for Sherlock Holmes

An RStudio plot of frequency by index (rank) for words in for Sherlock Holmes

b) Make observations about the distribution of the frequencies.

As we can see in the plot, the words that have a low index (occur at the top) in the frequency list have a very high frequency. The single most frequent word has an index of 1 and a frequency of over 700 occurences, while the second most frequent word occurs about 550 times. There is a very long tail of words that are only used once or twice.

c) The picture can be made clearer by using a logarithmic y-axis. Try plot(Frequency,log="y") instead. Then try making both axes logarithmic with log="xy".

Word frequency by index with a logarithmic x and y axis

Word frequency by index with a logarithmic x and y axis

This plot indicates more clearly that there is an exponential relationship between a word’s index in the frequency list and the number of occurrences. This generally means that the most frequent word (index 2) is approximately twice as frequent as the second most frequent word, and three times more frequent than the third most frequent word, and so on and so forth.

d) Compare the result to the similar graph below, which shows word frequencies in different languages:

A plot of the rank versus frequency for the first 10 million words in 30 Wikipedias (dumps from October 2015) on a log-log scale.

A plot of the rank versus frequency for the first 10 million words in 30 Wikipedias (dumps from October 2015) on a log-log scale.

Obtained from Wikipedia.org on 30.01.2021

The graph shows that the observations we made from plotting the Sherlock frequency list holds true for most languages. Zip’s Law roughly states that the rank (index) of a word in a frequency list is inversely proportional to its frequency.

Exercise 1.3: N-grams

a) Execute these commands on a larger tokenized file. Create a frequency list of the resulting bigrams.

There’s a very large text file you can use here. You will of course need to tokenize it first :)

Creating a frequency list for bigrams in The Bible

Creating a frequency list for bigrams in The Bible

b) Create a list of trigrams for the same file. Compare the number of trigrams with the number of bigrams.

Creating a list for trigrams in The Bible and comparing the number of bigrams to trigrams

Creating a list for trigrams in The Bible and comparing the number of bigrams to trigrams

Okay, so the number of bigrams is equal to the number of trigrams? That doesn’t make sense. What’s going on here…?

Comparing the number of bigrams to trigrams

Comparing the number of bigrams to trigrams

Ah, when using tail instead of head we see why it counted the same number of bigrams and trigrams. For bigrams, there is a single line which isn’t actually a bigram. For trigrams, there are two lines which don’t contain trigrams. This is because the paste command kept on pasting empty space when one of the files we gave as input had reached the end.

In conclusion, for The Bible the total number of bigrams is 994,514 and the total number of trigrams it’s 994,513. In general, if \(X = \text{The number of words in a given sentence K}\),

then the number of N-grams for sentence \(K\) would be calculated as:

Part 2) Ciphers and string substitutions

Exercise 2.1: Ciphers

a) Create a script decrypt.sh which turns the ciphertext produced by Koenraad’s encrypt.sh back to normal.

The following workflow should give the original file: source encrypt.sh < chess.txt | source decrypt.sh

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

#!/usr/bin/env bash

# decrypt.sh

normal='qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmQWERTYUIOPASDFGHJKLZXCVBNM'

decrypted='a-zA-Z'

tr $normal $decrypted

b) Extend the strings to include the characters æøåÆØÅ (if your implementation of tr supports multi-byte characters), and also digits, space and punctuation. Consider a less systematic ordering of the characters in the second string.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

#!/usr/bin/env bash

# encrypt-improved.sh

normal='abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzæøåABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZÆØÅ'

decrypted='qkQeæfAJUHGORwTYødjPÆSWiXåxZLyItnØFbpgcÅoMvKsDazVCulrEhBmN'

tr $normal $decrypted

Exercise 2.2: String substitutions

Reproduce the lecture example code and extend the amount to include numbers with a decimal point, such as 289.90, and change the replacement so that it converts the decimal point to a decimal comma.

1

2

3

$ sed -E 's/kr\.? ([0-9]+)([\.,])?([0-9]+)?/\1,\3 kroner/g'

kr. 140.50

140,50 kroner

Type

cmd + corctrl + cto exit thesedprogram.

Exercise 2.3: String substitutions (2)

a) Some accented vowels are missing from the example in the lecture notes. Add them.

First we need to edit the tokenize.sh-script to include accented characters in Spanish. Don’t forget ñ and ü! (Though I think only a handful of Spanish words use the ü…)

1

2

3

#!/usr/bin/env bash

# tokenize.sh

tr '[:upper:]' '[:lower:]' < $1 | tr -cs '[a-záéóíúüñ]' '\n'

Next, we need to edit the sed expression to account for accented vowels. In this case, we don’t want to include the ñ. I also added another i to the second group, because there is a word (gui) where the u is part of the onset, not the nucleus.

1

$ sed -E 's/[aeiouáéóíúü]+/,&,/' mono-es-tokens.txt | sed -E 's/,([iu])([aeoáéóíúüi])/\1,\2/' | head

b) Replace empty onsets or codas with 0.

Here, we simply add another substitution to the expression. You can replace the leading commas in the beginning of a line with 0, with sed -E 's/^,/0,/', like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

$ sed -E 's/[aeiouáéóíúü]+/,&,/' mono-es-tokens.txt | sed -E 's/,([iu])([aeoáéóíúü])/\1,\2/' | sed -E 's/^,/0,/' | head

0,a,

0,a,l

0,a,r

0,a,s

0,a,x

b,a,h

b,a,r

b,e,

b,e,l

bi,e,n

c) After reading the chapter on cutting columns, cut the vowel column from this comma-separated output and produce a graph of the frequencies of the vowels.

I’m just going to continue to add more code to the existing expression, even though you might want to save the output from the previous exercise to a file before you progress further. Anyway, this time we add the expression cut -d',' -f2 to the pipeline. The -d',' flag sets the delimiter to comma, while the -f2 flag tells cut to extract only the second field.

PS: We could’ve used

awkinstead ofcuthere. Remember how?

1

2

$ sed -E 's/[aeiouáéóíú]+/,&,/' mono-es-tokens.txt | sed -E 's/,([iu])([aeoáéóíú])/\1,\2/' |

sed -E 's/^,/0,/' | cut -d',' -f2

We want to count the frequency of each vowel, so we add the familiar expression sort | uniq -c | sort -nr to the pipeline as well:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

$ sed -E 's/[aeiouáéóíú]+/,&,/' mono-es-tokens.txt | sed -E 's/,([iu])([aeoáéóíú])/\1,\2/' |

sed -E 's/^,/0,/' | cut -d',' -f2 | sort | uniq -c | sort -nr

63 a

57 e

50 o

36 i

27 u

7 é

3 í

2 á

1 y

1 ú

Our goal is to produce a graph of the frequencies of the vowels. In order to do that, we first need to save the output to a comma-separated values (.csv) file. A .csv file is just like a text file where the columns are separated with a comma, so we can use awk '{print $1","$2}' or sed -E 's/ *([0-9]+) /\1,/'g to replace the spaces in the output with commas. We’ll then save the final output to a file, here named es-vowels-freq.csv:

1

2

$ sed -E 's/[aeiouáéóíú]+/,&,/' mono-es-tokens.txt | sed -E 's/,([iu])([aeoáéóíúi])/\1,\2/' | sed -E 's/^,/0,/' |

cut -d',' -f2 | sort | uniq -c | sort -nr | awk '{print $1","$2}' > es-vowels-freq.csv

Almost there! Finally, we can plot the frequencies in RStudio:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

freqlist <- read.csv("es-vowels-freq.csv",

fileEncoding = "UTF-8", header=FALSE)

names(freqlist) <- c("Frequency", "Character index")

attach(freqlist)

barplot(freqlist$Frequency, las=2, col='darkgreen', xlab='Character',

ylab='Frequency')

And the output should look something like this:

The frequency of vowels in the file mono-es.txt

The frequency of vowels in the file mono-es.txt

Feel free to experiment further with different parameters, plot styles, labelling etc! For example, you can try to add a label to each bar with the character that the bar represents. I.e, the first character is a, the second is e, and so forth.

Part 3: Additional exercises

Exercise 3.1: Word frequencies

a) Tokenize The Bible and save it to a new file bible-tokens.txt.

If downloading the file from MittUiB doesn’t work, you can copy the plaintext of The Bible directly from The Gutenberg Project here.

To tokenize the file, we can use the tokenize.sh script from the lecture notes.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

$ source tokenize.sh the-bible.txt > bible-tokens.txt

$ head bible-tokens.txt

the

project

gutenberg

ebook

of

the

bible

douay

rheims

old

b) Retrieve all words from bible-tokens.txt which contain the letter “A” (case insensitive) non-initially and non-finally. Get the frequencies for these words and sort them by highest occurrence.

The simplest way to do this is probably by using egrep:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

$ egrep -iw '[^a][[:alnum:]]+[^a]' bible-tokens.txt | head

the

project

gutenberg

ebook

the

bible

douay

rheims

old

new

We have a shell script freqlist.sh from earlier which we can use to get the frequencies. It looks like this:

1

2

3

#!/usr/bin/env bash

# freqlist.sh

egrep -ow '\w+' $FILE | gawk '{print tolower($0)}' | sort | uniq -c | sort -nr

So a final solution could look like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

$ egrep -iw '[^a][[:alnum:]]+[^a]' bible-tokens.txt | source freqlist.sh

79636 the

16117 that

11695 shall

10664 his

10120 for

9049 they

8542 not

8472 lord

8171 him

7647 them

...

c) Use egrep to only retrieve words from bible-tokens.txt that are five letters long or more, then count and sort them like above.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

$ egrep -iw '\w{5,}' bible-tokens.txt | source freqlist.sh | head

11695 shall

5252 their

4482 which

2760 israel

2735 there

2499 people

2176 things

2048 before

1929 children

1926 against

d) Out of all words in the text, how many percent of them are five letters or longer and used more than once?

1

2

3

4

$ egrep -iw '\w{5,}' bible-tokens.txt |source freq-list-improved.sh | awk '{sum+=$1} END {print sum}'

313841

$ wc -w bible-tokens.txt

994536

We can calculate the answer with the following formula:

\[\dfrac{\text{amount of long words which occur more than once}}{\text{total number of words in the text}}\]So the answer is 313841 / 994534 = 0.315= 31.5%

e) Write a shell script that can take a regular expression (argument $1) and a file name (argument $2) from the user, and output a frequency list like in the exercises above.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

#!/usr/bin/env bash

# freqlist-with-regex.sh

# Tokenize the input file

egrep -iwo '[[:alpha:]]+' < $2 | awk '{print tolower($0)}' |

# Extract matches with egrep and the regex input from the user

egrep $1 |

# Output a frequency list

sort | uniq -c | sort -nr

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

$ source freqlist-with-regex.sh '^lead.*' ../the-bible.txt

72 lead

30 leadeth

29 leader

8 leaders

7 leading

3 leadest

2 leads

Exercise 3.2: N-grams

a) Find all trigrams in chess.txt containing the word “det”. Afterwards, find only trigrams containing “det” as the first word, middle word, then last word.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

$ tail -n+2 chess-tokens.txt > chess-next.txt

$ tail -n+3 chess-tokens.txt > chess-next-next.txt

$ paste chess-tokens.txt chess-next.txt chess-next-next.txt > chess-trigrams.txt

$ egrep -w 'det' chess-trigrams.txt | head

er det allerede

det allerede remis

nrks studio det

studio det var

det var spilt

brettet ja det

ja det var

det var raskt

til nrk det

nrk det gikk

Finding trigrams containing det as the first word:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

$ awk '{if ($1=="det") print $0}' chess-trigrams.txt

det allerede remis

det var spilt

det var raskt

det gikk inn

det er ganske

det spilles mange

As the second word:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

$ awk '{if ($2=="det") print $0}' chess-trigrams.txt

er det allerede

studio det var

ja det var

nrk det gikk

får det er

slitsomt det spilles

And the third:

1

2

3

4

5

6

$ awk '{if ($3=="det") print $0}' chess-trigrams.txt

nrks studio det

brettet ja det

til nrk det

jeg r det

ganske slitsomt det

b) Why can it be useful to differentiate where the word occurs in the N-grams?

N-grams are used for a lot of different things in natural language processing. For example, we might use N-grams for calculating word probabilities in auto-complete or automatic spell checking. By differentiating where the word occurs in the N-gram, we can calculate different probabilities for related words. So if a user types on my, we can look at which words occur most frequently as the third word in a trigram with those two words. Thus we might be able to predict that the user wants to write on my way.

This is just one example. Can you think of any others?

Exercise 3.3: String substitutions

Using sed, create a shell script which reformats dates written as DD.MM.YYYY to YYYY-MM-DD.

1

2

3

4

#!/usr/bin/env bash

# year-formatting.sh

sed -E 's/([[:digit:]]{2}).([[:digit:]]{2}).([[:digit:]]{4})/\3-\2-\1/g'

Let’s test our script by giving it the file birthdays.txt as input:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

$ # Let's view the original file contents first

$ cat birthdays.txt

BIRTHDAYS

----------------------

Roger 22.08.1992

Michael 25.02.1997

Bob 15.01.2000

Lindsey 18.12.1994

Jessica 21.10.2001

Jeff 30.03.1976

Trevor 08.15.1989

Louanne 06.07.1965

Tim 01.02.1972

---------------------

$ # Then we perform the substitution with our script

$ source year-formatting.sh < birthdays.txt

BIRTHDAYS

----------------------

Roger 1992-08-22

Michael 1997-02-25

Bob 2000-01-15

Lindsey 1994-12-18

Jessica 2001-10-21

Jeff 1976-03-30

Trevor 1989-15-08

Louanne 1965-07-06

Tim 1972-02-01

---------------------

$ # We can also choose to save the output in a new file

$ source year-formatting.sh < birthdays.txt > birthdays-reformatted.txt

$ cat birthdays-reformatted.txt

BIRTHDAYS

----------------------

Roger 1992-08-22

Michael 1997-02-25

Bob 2000-01-15

Lindsey 1994-12-18

Jessica 2001-10-21

Jeff 1976-03-30

Trevor 1989-15-08

Louanne 1965-07-06

Tim 1972-02-01

---------------------